Description

“Ron Manners is one of those unique people that you meet once in a lifetime. His spirit and courage is inspiring, and his latest book ‘The Lonely Libertarian’ is a testament to that. His is a typical David v Goliath story, and I highly recommend it for anyone who wants to learn how they too can make a difference.”

Naomi Brockwell

“This is more than just a book; this is a rallying point for future generations!”

The Mannwest family business, continuously operating since 1895, has the been the launch-pad for many of Ron’s ‘heroic misadventures’ that have taken him on numerous adventures and through many ‘booms and busts’. These experiences have given him an understanding of money and its usefulness. “Money is a real friend if you can put it to work usefully”.

From the Foreword

To travel is to grow…

It is a long way in distance, culture and perspective from the wide, parched expanse of Australia’s ‘outback’ Kalgoorlie, to the narrow winding paths up the Peak in humid Hong Kong. It takes special insight to love both cities and explain the reasons why that sense has a common cause.

Ron once observed that neither Kalgoorlie nor Hong Kong was a “cry baby city”. He elaborated that both were subject to world prices for their goods, be it gold, nickel, elaborate manufactures or human talents. When prices change, these cities have no choice but to adapt, seek new horizons and thereby transform themselves. They don’t have the luxury of standing still. They discover and assemble what is needed for success with new prices in a different world.

That unusual transcendence of their economic base comes from values of self-reliance. Survival, dramatic change and progress for both cities don’t come from benevolent government, but from adaptation by individuals and their enterprises, despite the impediments of governments and the self-proclaimed wisdom of misguided intellectuals.

The personal escapades of Ron Manners exemplify these city’s tales of success against the odds. As Don Boudreaux wrote in the introduction to Heroic Misadventures, Ron is a “searcher”, but more than that he has been an assembler of the skills, connections and resources internationally that he has needed for a personal mission exemplified by Leonard Read’s phrase “education for one’s own sake”.

Those who cherish liberty and self-education will find this work an invaluable resource as they seek to adapt to a changing world where the right for individuals to pursue “anything that’s peaceful” seems ever more under threat.

Bill Stacey

Inaugural Chairman, Lion Rock Institute, Hong Kong, August 2019

Extended Appendix

-

POEM: Why I Talk to Kelpie Dogs

-

PART I: Starting Out!

- 1. Why the lonely theme?

- 2. Turning accidents into opportunities

- 3. Why didn’t someone tell me (life has no shortcuts)?

- 4. Mannwest’s 124-year journey as a family firm

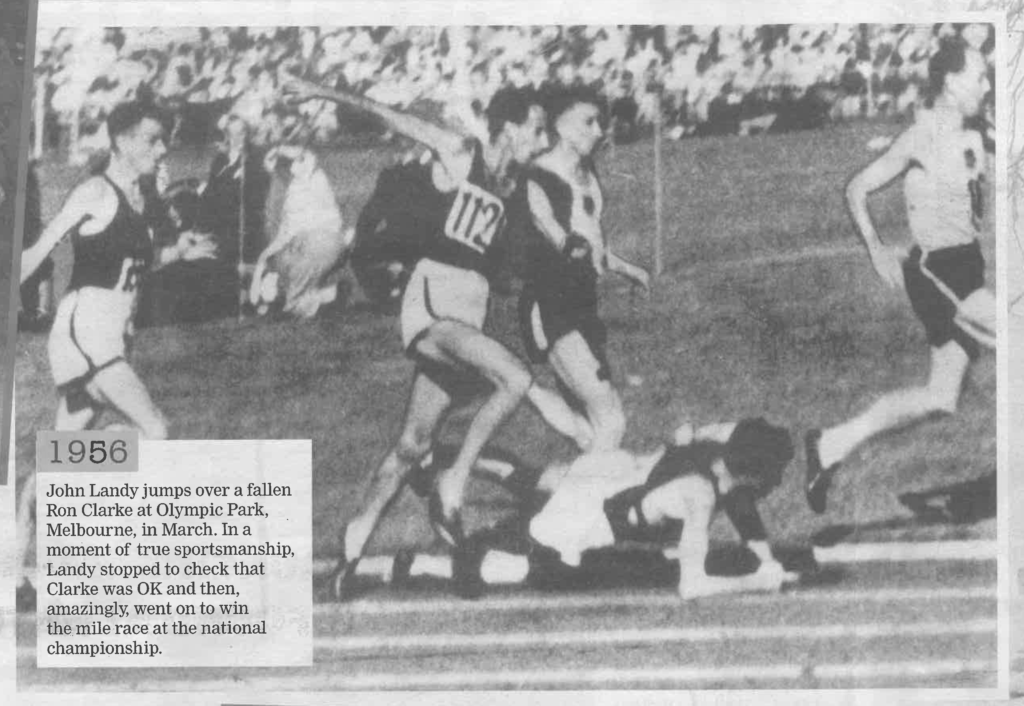

- Ron Clarke: Remembering a humble champion whose flame will forever burn bright.

-

From the West Australian January 26, 2021

- 5. Northern Australia: the next powerhouse of the global economy?

-

PART II: My ‘Fugitive’ Years (1975-1982)

- 6. The alienated Australians

- 7. Adventures in taxation (help feed a starving bureaucrat)

- The below files are available for viewing at our office in Subiaco. Please call (+61) 08 9382 1288 to make an appointment.

-

PART III: Mining – ‘Turning Ideas Into Gold’

- 8. Triumphs and tragedies of Australia’s mining industry: 1960’s – 2015

(The birth of Australia’s nickel industry) - 9. Croesus Mining (Playing a part in Australia’s great gold renaissance)

- 8. Triumphs and tragedies of Australia’s mining industry: 1960’s – 2015

-

PART IV: ‘Turning Gold Into Ideas’

- 10 Russia; ‘Seven days that shook the world’ (Sept. 1990)

- 11 Liberty could be good for you too!

- HRH Prince Philip: Ideas Have Consequences – Ron Manners 2017

- A Prince Replies to Machiavelli: Philip of England on the Erosion of Freedom

- The Duke of Edinburgh, “Intellectual Dissent and the Reversal of Trends” in Confrontation: will the open society survive to 1989? pp 199-218, The Institute of Economic Affairs, 1978

No Comments

Ron, just finished your great book. Bloody marvellous, a great read. If we want to define enterprise, we need only two words – Ron Manners. And nothing could be better than your cover photos of heaps of bright young people given half a chance to strike out into real life.

The Austrian émigré economist Friedrich Hayek didn’t much like the label “libertarian”, which he considered a “singularly unattractive” Americanism. He preferred to call himself “an unrepentant Old Whig—with the stress on the ‘old’”. Old or young, he certainly was not lonely. When he founded the Mont Pelerin Society in 1947, he and his comrades (well, associates) numbered thirty-nine of the world’s most prominent intellectuals. Then again, there were no women invited to that first meeting in Switzerland, so perhaps the Old Whigs were lonely after all.

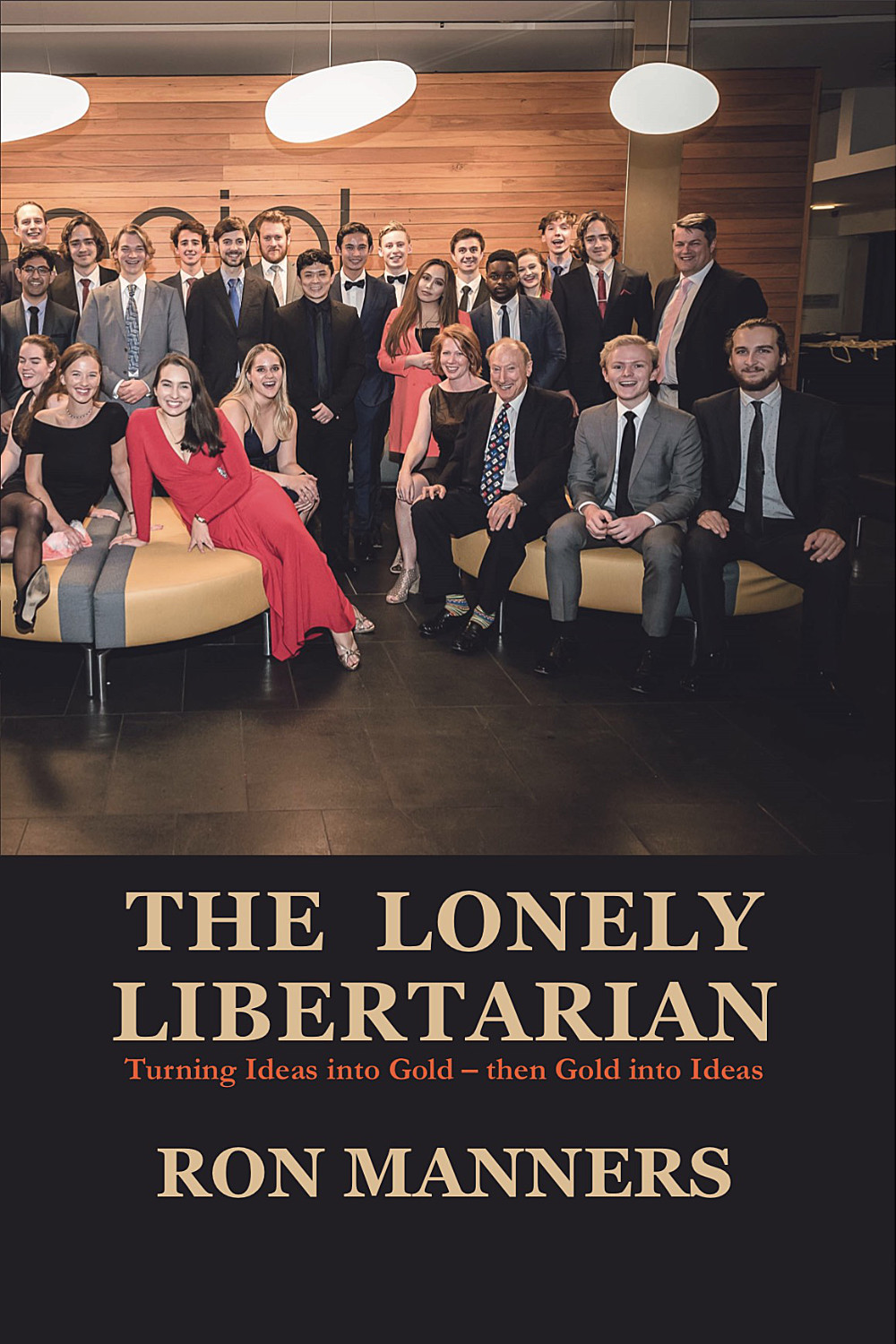

If there’s one message about Ron Manners that comes through loud and clear in his second memoir, The Lonely Libertarian, it’s that he’s rarely alone. The very cover of the book depicts him surrounded by twenty-four young Mannkal Scholars, participants in the flagship educational exchange program of the Mannkal Economic Education Foundation, set up by Manners in 1997. Mannkal is a portmanteau of Manners and his hometown of Kalgoorlie, though the foundation is sensibly headquartered in Perth.

Which is not to say that Manners has lost his connection to his origins. Far from it. Throughout The Lonely Libertarian, Manners gives us glimpses of family loyalty and corporate commitment, and though it is impossible for an outsider to verify these, it is certain that Manners himself believes that friendship and good cheer are the keys to success. Not that he necessarily defines “success” in business terms. The Lonely Libertarian reads much more as a philosophy for living than as a guide to getting rich.

The book itself is something of a hodgepodge, or to be kind, an “eclectic collection”, a treasury to be dipped into rather than a monograph to read straight through. Part Boy’s Own adventure and part Horatio Alger tale, Manners’s life seems to belong as much to the nineteenth century as to the twenty-first. He seems to have missed the twentieth century entirely, or at least to have dodged its zeitgeist. He went straight from the mining frontier of Western Australia to the electronic frontier of online activism.

Manners tells the story—or stories—of his life, from his far-from-boring bush upbringing (What was there to do for fun in 1950s Kalgoorlie? “We shot things and we blew things up”) through his years as a tax fugitive (or financial conscientious objector?), to the founding of (“rich as”) Croesus Mining and his (unsuccessful) adventures in Russian reform. Manners emphasises the role of accidents and the lessons to be learned from them; one suspects that he has courted accidents more than most. But the real lesson of this book seems to be to go the extra mile to connect with other people. More often than not, they’ll welcome the approach, and connect right back.

Two teenage accidents, one serendipitous and the other almost tragic, set Manners on the course to the not-so-lonely libertarianism of the book’s title. The first was the chance discovery of old magazines from the libertarian Foundation for Economic Education, which led to a lifelong association with its founder, Leonard E. Read, after the young Manners reached out to ask his editorial advice. The second was a car crash that nearly took off his right arm. His father refused to accept the doctor’s advice to amputate, teaching Manners the importance of questioning authority—and salvaging his second career as a multi-instrumentalist jazz musician.

Though always fun and full of good humour, the book is frustratingly uneven and poorly polished. One third of the book is given over to a single, bloated chapter on taxation, which consists of a random collection of stories, quotations, memoranda, vignettes, advice and plain old complaints about taxes. Some of these are quite entertaining; others fall flat. But good or bad, the main problem is that they are unorganised. If Manners kept his tax records this way, it’s no wonder that he got into trouble with the taxman! But he returned to the fold in 1982, and he says he’s been a happy taxpayer ever since.

The rest of the book is … pure gold. Some readers may disagree with Manners’s philosophy of governance, or even his philosophy of business, but no one will disagree with his philosophy of life, which might be summarised as something along the lines of “go your own way; you might just find others going the same way, too”. In his Russia chapter, Manners tells the story of how, in 1990, a Moscow street artist was moved to emotion because she “saw the outside world through [his] eyes, and … now she is sad because she will never know that world”. He should track her down and give her a copy of this book. The Lonely Libertarian lets us see the world through Manners’s eyes, and what a wonderful world it is.

This review was originally published in Quadrant Magazine.

The Lonely Libertarian is a dazzling book of hope for the future. Above all it reveals that one of the best investments that any of us can make is the investment in well founded ideas, in particular, good ideas that will flush the bad ones out of the system. Ron , unlike most in government, has actually had decades of business experience, risking his money, investing his money, working hard, knowing his business, and employing people that he paid, a kindred spirit. Someone who, like myself, understands that government tape and high taxes don’t help productivity, or Australia, and understands how reducing both would benefit Australians, just as it has benefited citizens of the USA , Singapore and India. He further understands that Australia has to be cost competitive and reliable to successfully sell its produce internationally, as we need to be able to do. Government taxes and tape, do not assist Australians in being internationally cost competitive, and yet not enough people, especially those without business experience like Ron, understand this. Good on you Ron. You’re one of Aussie’s best.

I faced the task of writing a review of this book with a high degree of trepidation. My first reaction

when the gregarious, bon vivant ex-miner, told me he was writing a book on loneliness, was one

of curiosity. How could he be lonely? When I now see the full title and read his explanation, it

starts to make sense. There are many exponents of minor political philosophies that find

themselves on the outside of the general popular discourse. Ron may object to the word “minor”.

My continuing trepidation stemmed from knowing that Ron was aware that our views were not

well aligned. I am not a libertarian. Although I spent my later years self-employed, I had for years

held senior positions in local government and therefore qualified as one of the bureaucrats that

he dealt with harshly in many sections of his book.

Ron’s convictions, as he records them, started early; more particularly with his father’s example

of not taking the word of experts without further query or investigation. He developed an early

interest in economics and, after a disrupted education, furthered his studies with the Kalgoorlie

School of Mines. Underlying the formation of his political philosophy was the influence of his

beloved Kalgoorlie. A case of – work for it – no easy way forward. It is very different today but

there can be no denying that it had an influence on many Western Australian natives. Many

families take pride in revealing their connection with the early goldfields. My mother was born

in Boulder.

He cites his early mentors as Leonard E. Read, at the time, President of the Foundation for

Economic Education in New York, Nobel prize-winning economist F.A. Hayek and Professor of

Philosophy John Hospers. He maintained an ongoing friendship with these illustrious academics

for many years.

Interestingly, the fourth person he refers to as having had an influence on his professional life is

Prince Phillip. Interesting because Phillip does not attract many positive references. Ron tells of

having been one of a hundred participants in an exercise initiated by Phillip whereby a disparate

group from business, unions and government were put together residentially and in organised

discussion for three weeks. This resulted in a level of understanding and cooperation which

could never have been achieved in any other way. It continues to bear fruit today, years after

the event. A very well thought through idea. Ron has since had correspondence exchanges with

Phillip and holds him in high regard. How he came to make the connection with these people

and exchanged views with them for many years, makes interesting reading.

His association with Read’s Foundation for Economic Education lead Ron to establish the

Mannkal Economic Education Foundation. It, unashamedly, charges its young students to follow

“economic and political philosophical principles that promote the virtues of individual

responsibility”. The participants are recruited from the universities and they go through a

screening process before being selected for scholarships to attend conferences and study

overseas. Some 1500 young people have been through the program and the cover of the book

would indicate that there is very little evidence of loneliness among these libertarians!

At the end of the nickel boom, Ron clashed with the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) over being

taxed for profit on shares which he was not able to sell. This was the start of a long acrimonious

exchange with 10 to 20 percent interest being charged on the outstanding amount. He left

Australia for seven years, leaving the amount unpaid. He was clearly the wrong person to upset

in this way. From there, he has made it a lifelong endeavour to examine ways of highlighting the

“illegality” of taxation and the constraint on freedom caused by the central planning of

government in Australia. His dedicated move towards libertarianism stemmed from this seven

year exile. He returned to Australia and the tax paying workforce after a truce with the ATO which

lead to the expunging of the old debt.

This book is a potpourri of addresses he has given to conferences and workshops over the years,

tied together with anecdotes of his colourful life. Into that, as a theme, is a strident and detailed

attack on taxation. His contention is that it is a form of theft and the government, through its

politicians and bureaucrats, is the villain of the exercise. He proposes and endorses any form of

tax evasion or avoidance, lauding tax resistance programs and toying with the idea of a revolt.

This plays well to his disciples and to the broader libertarian industry. Chapter 7 dealing with

taxation was written in 1978, at the end of his self-imposed exile and comprises a major portion

of the book.

Ron launched the book seven times in different states of Australia plus Hong Kong, New York,

and London. On each occasion the audience was drawn from an organisation affiliated to the

libertarian cause. They varied in that each seemed to see in the book an aspect of the philosophy

that appealed to their emphasis. For example, in London it was seen as “demonstrating the

results of investing in the next generation”. Whilst in Sydney it was described as “an example of

standing up straight against the Australian Taxation Office”. In Hong Kong the launch was at the

Lion Rock Institute and it was described as “a book by an Australian about Hong Kong”.

This review would be lacking if mention was not made of Chapter 10 where Ron records the

details of a week in Russia in 1990, attending a series of seminars and workshops with forty

international academics, economists and businesspeople. They were there to explain the free enterprise

system that may be available to them soon. The timing was amazing. It was the seven

days that shook the world. His take on this experience and what life in Russia was like at that

time, makes very interesting reading.

Returning to the title of the book, one must conclude that the personality of the author and his

propensity to seek out and engage people of interest to his quest for knowledge, would belie any

suggestion of loneliness. He has brought together many of his literary efforts to interest and,

perhaps educate, attendees at conferences and gatherings around the world.

I read with interest your book over the break; in particular, I enjoyed learning more about Ron Manners both your story and your philosophies in life. Resilience, flexibility yet knowing when to draw a line in the sand, and the importance of relationships resonated well. Your life has been and continues to be colourful and productive. Congratulations on putting it on paper for others to enjoy.

There are just so many tips in there – maxims of experience as I would term them!

Anyway you have made much of your life – and you’re still achieving! Well done, Sire.

Thanks for your “Lonely” book. It is full of fun and pithy advice. The gold mining story is engaging, less so is the tax story. I like the picture of the newsboy: he looks too young to know what is the correct change when a three pence coin is offered for a twopenny newspaper.

I am impressed with the clarity that you explain the early loneliness of making your own decisions. Too many people just follow the crowd. Also, whilst aware of “rent seekers’ I had not previously been aware on “Public Choice Theory”, that fits my desire to understand the academic background.

New Zealand having previously been (part) libertarian and democratic allowing qualified women and non-white to rise to the top, is now going through a process that transfers assets (including land and water) from democratic organisations (local councils, government agencies) to tribal organisations lacking even internal democratic process. Clearly not in the interest of the majority. A justification we hear on the news is “the tyranny of the majority”.

That said, the ACT party (Association of Companies and Taxpayers) led by David Seymour is close to being genuinely libertarian, and almost certain to be in coalition to form the next government replacing Ardern.