I presented this speech at the 2018 Mont Pelerin Society General Meeting in Gran Canaria, Spain. It was held September 30 to October 6.

Lessons in liberty

Liberty has been good for me and today is a classic example. Here I am, with three individuals, of whom I have heard so much, not imagining that I would ever meet them personally. The liberty movement has brought us together and I find myself seated alongside them today. So, I say again, thank you to Gabriel and his wonderful team for arranging such a great meeting here in Gran Canaria.

Most of my life has been spent searching for nickel and gold, finding it, mining it, pouring gold bars and marketing them. Let me assure you that the experience of holding your first gold bar is equivalent to a mother holding her first born or an author holding his first published book. Mind blowing!

However, instead of talking about that today I will mention a few chance meetings, like today, that have opened up my life to incredible opportunities that I have seized enthusiastically.

There have been many individuals, whom I regard as teachers, who have made a vital difference to my life but today I will mention only four. These four individuals reinforced my belief that good ideas flow upward, rather than sink downward.

The famous four

Any successful companies that I have run have always been ‘bottom-up’ management style and not ‘top-down’ dictatorships. I suspect that socialism is winning the battle of ideas, today, by focusing on promises to the individual. Our free-marketeers focus on fixing nations or the world and expecting individuals to believe there will be a few crumbs left over to ‘trickle down’ for them.

I always focus on telling the younger generation how good the liberty movement has been, for my career, rather than the big picture which always seems so far away. So to succeed, let us focus on the individual. Absurd, as it may seem, our free market movement has, in many ways, been focusing on the ‘collective’.

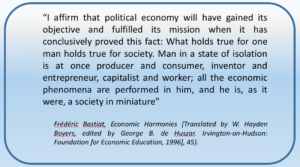

Let me refer to that wonderful challenge posed to us by Frederic Bastiat, so many years ago:

Now let me mention these four outstanding individuals in my life: Leonard E Read, John Hospers, FA Hayek and Prince Philip.

Leonard E Read

My world of the free market and how I have met so many interesting people, started when I was 16 years of age. One afternoon, after high school, I was unpacking large engineering machinery crates from America in the back of my father’s mining engineering business, in Kalgoorlie, an Australian mining town.

I found some old packing material which turned out to be the Freeman Magazine from the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE). These were all crumpled up. As you might imagine this was many years before the advent of bubble wrap being used as packing material.

I spread these, very crumpled magazines, at home that night and was electrified to read the contents about free markets and individual responsibility. I can still remember the exhilaration of these new thoughts.

Then, three years later, as the Editor of the School of Mines Magazine, I started publishing some of this material, an Australianized version of these free market ideas. I was almost run out of town because Kalgoorlie was pretty much a union-controlled town and the thought of being able to make it on your own without using union muscle to push the other guy around was not even to be considered.

I wasn’t doing so well so I contacted the President of the Foundation for Economic Education, Leonard E Read, and explained to him that their ideas were getting me into trouble.

He politely wrote back explaining that these ideas really started with Aristotle and had been polished up over the years. He suggested that if I was having trouble defending myself against these antagonistic voices it just meant that I had not spent enough time understanding my own position.

With that in mind, he sent me some books, put me on his mailing list and that started our amazing relationship. Leonard E. Read became my mentor over many years.

In 1982, some 30 years later, he invited me to FEE’s office, in Irvington, New York, to speak to his Board of Directors and tell them the story about these ‘packing boxes’. I told him that was a fairly ordinary story to be telling but he suggested that if I started the story he would finish it off.

He finished off by saying: “colleagues, our motto for the Foundation for Economic Education, is that ideas have consequences. We produced this small magazine and it went to the Timken Roller Bearing Manufacturing Company and then down through all the staff and ended up in the packing department. It was crunched up as packing material and sent off to the other side of the world where this young man smooths it out and goes on to form his own think tank based on the Foundation for Economic Education.”

Gentlemen, our ideas have more consequences than we had ever dreamt of. (Those of you who remember Leonard E Read, as one of the founders of the Mont Pelerin Society, can remember what a good story-teller he was.)

This was the start of an adventure and I could spend a full day passing on some of these snippets of wisdom that Leonard Read passed onto me, over the years. Leonard Read, by replying to my letters, opened up my world which is why I try very hard to reply to every letter or email that I receive.

Leonard Read introduced me to my first Mont Pelerin General Meeting, in Hong Kong, 1978. So, 40 years later, here we are in Gran Canaria.

Professor John Hospers

This, I describe, as the unlikely but lasting friendship between me, the prospector and John Hospers, the philosopher. My connection with John Hospers dates back to 1961 when I was still living in Kalgoorlie. I was then studying electrical engineering at the School of Mines.

So what has that got to do with philosophy? Let me tell you how I became interested in philosophy.

Around 1960 Hugh Hefner launched his Playboy magazine. My mother saw me with that magazine and suggested that I should not look at the pictures, so, being a totally obedient young boy, I only read the articles.

Hefner’s monthly editorial was called the Playboy Philosophy. If this was philosophy I decided I would like to get more of it. So I enrolled in an external philosophy unit, by mail, with the University of Western Australia.

I enjoyed the course and was particularly captured by the text book ‘An Introduction to Philosophical Analysis’ by Prof John Hospers, then of the University of Minnesota. I liked the way Prof Hospers’ mind worked; I started corresponding with him and we became life-long friends.

What led me to write my first letter to John in September 1961? My initial reason was entirely non-academic, as I just wished to share with him what I thought to be a very strange article that appeared in Australia’s most un-academic weekly magazine called Pix.

On that September day I was seated in a barber’s shop reading a trashy magazine describing an ‘unspeakably evil’ textbook. Among other things, it proclaimed that ‘young students in Australian universities are being taught an evil philosophy from an evil textbook’. I suddenly realised that this was exactly the same philosophy textbook that I had just completed (without detecting any sign of evil).

What had I missed?

That night, skimming through the book again (with the torn-out pages from the magazine)…I realised that the writer of that article had interpreted as ‘evil’ what I had admired about the book—namely, a sense of advocacy for ‘heroic individual responsibility’ in the true Aristotelian sense.

After worrying about this misinterpretation for another 15 minutes, I wrote and asked Prof Hospers if I had missed something. Or was there, perhaps, another later edition that contained all this ‘sinful’ material?

His response was measured and polite. He indicated that any academic who had a view on anything in particular was open to attack from time to time—often from surprising quarters.

This magazine article was the subject of one of our later personal discussions and I suspect that he took this into account when he produced his 1996 book, Human Conduct: Problems of Ethics, where he expanded on the concept of personal responsibility in chapter 9 – ‘Punishment & Responsibility’. John was forever focused on clear thinking and clear writing.

The single point upon which the Pix article critic appeared to be fixated was their interpretation that John was promoting promiscuity. My interpretation was that John was advocating the virtues of personal responsibility.

Apart from thoroughly enjoying John’s book during my philosophy study year, I often had occasion to refer to it throughout my life.I clearly remember one occasion when I referred to John’s definition of ‘beautiful’. (Chapter 8, page 497)

This was during my time managing a hotel in Bali when I noted that the staff repeatedly burst into laughter every time an Australian guest described their food or a meal as ‘beautiful’. The staff then explained to me that only Australians describe food as ‘beautiful’ and, to them, the word was reserved for many other things, but never for food.

Hospers would have approved of the use of ‘beautiful’ in respect to food. As he said: “We are generally inclined to speak of objects as ‘beautiful’ when they arouse in us aesthetic experiences.”

In 1997, at one of our meetings, John handed me a copy of the fourth edition of his Introduction to Philosophical Analysis. It was clear that he had made many changes as he refined his own thoughts and, in my view, managed the herculean task of editing his own work. The fourth edition totalled 282 pages in place of the third edition’s 532 pages.

One point of difference between the editions I can recall immediately.

One of the new sections (Chapter 4) was ‘The Way the World Works: Scientific Knowledge’. I particularly enjoyed the subsection of that chapter titled ‘A theory in geology’. Of geological theory he remarked: “We turn now to another theory, which includes data from astronomy and biology, with one science reinforcing the observational data of other sciences to form a coherent, unified theory.”

This new section might explain the personal following that John developed among earth science professionals.

Back in 1961, little did I know that, 12 years later, John Hospers would be the first Libertarian Party US presidential candidate or that I would become his life-long friend right through to his death in 2011, at the age of 93. Fifty-seven years later, I’m exchanging views with his other fellow students, all over the world. We are grateful that he taught us how to think with clarity and develop our own personal philosophies—something which has assisted each of us over so many years. Each of our own John Hospers’ experiences will be published in a John Hospers commemorative book.

These fellow students are also contributing, in various ways, to republish updated versions of Hospers’ books, including his classic volume Libertarianism, as well as making available his remarkable correspondence with the leading thinkers of his time, including Ayn Rand.

During the 50 years between my initial exposure to John Hospers and his death in 2011 we corresponded and enjoyed time together in several remarkable places.

Let me mention just three occasions.

One: In 1984 we invited John to London as the keynote speaker for the second Libertarian International Conference. A VHS video of his talk is available at this YouTube link.

Two: Los Angeles meeting. One time, in the early 1980s, it appeared that we would be deprived of a meeting in Los Angeles. I was due to spend a day and night there on my way home to Australia, from New York City. There was an airline complication that reduced my time, in L.A., to four hours, confined to the airport. I rang John from New York and explained that he would have to settle for me telephoning him from the L.A. airport and as I only had four questions for him we could manage that as a consolation.

I clearly recall his response: “So, you will have four hours at the airport? Ron, you only have four questions for me but I have 20 questions for you so I will come to the airport and we can sit quietly for four hours.” This we did while consuming several drinks. John’s 20 questions were all focused on how I had come to the same conclusions on so many questions, as he had, but from a completely different direction. He had been writing about the threats of unrestrained government, and he saw me as someone, who had been put out of business three times by my refusal to join the cosy cartels of occupational licensing. I’m sure he saw me as a laboratory rat with blood still pouring from my wounds, so therefore a worthy subject for his study.

Three: The last time we met was in 2004 when he spent the full day with my wife, Jenny, and me as our ‘tour guide’ at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum in California.

For those who haven’t had the pleasure of visiting the Ronald Reagan Memorial Library let me mention that, in line with most US presidential libraries, it is financed entirely from private donations. The land, the buildings, the landscaping, even to Boeing’s donation of Air Force One, meticulously reassembled in the garden, are all privately funded.

The only exception being the underground vault which stores the official presidential papers. That is financed and securely managed by the US Federal Government.

On that full day, at that wonderful facility, John proved to be a magnificent tour guide. However, you can imagine my disappointment when we were refused entry into the official presidential documents under secure guard. The problem was solved when I called upon some John Hospers’ clear thinking and loudly announced that John was a former Presidential candidate. Well; a visit by three seemingly simple tourists was turned into something of a Royal visit. From that point on we were appointed a special research guide and shown every imaginable document, including the hand-written speeches of Ronald Reagan where he meticulously transformed run-of-the-mill speech writers’ documents into very personally focused speeches for which he was so noted. These are the documents that he was working on so late in the night when many democrats were laughingly describing him as ‘dozing off in the Oval Office in the later hours.’

A remarkable day and John had so much to contribute to our depth of knowledge of the nature of the deep spirit of loyalty for which citizens of the United States are renowned. Never one for pretence, John Hospers just wanted to be remembered as a teacher. His own words highlight his concerns for the criteria used by universities, even in those early days:

“I am mostly known as a writer of philosophy. But I always desired to be remembered as a great teacher. Universities, however, consider only a teacher’s scholarly works and not their teaching ability. I want to be remembered as a philosophical instructor who could clarify questions and present good ideas clearly, avoiding vagueness and confusion in the presentation of ideas. That is probably my main legacy as a teacher and many of my students have come to remember me in just that way.”

History has shown John Hospers to be a great teacher and I wonder if today’s students will think as kindly about one or more of their own lecturers in 50 years’ time.

It is difficult to conclude my memories of John Hospers in a manner that honours his own style, remembering also that he always liked to leave us with a challenge. So, I will let John conclude with the final words from his Libertarian International Conference presentation in 1984:

“There are now hundreds of books and articles demonstrating the superiority of the free-market, as well as books such as Ayn Rand’s espousing their philosophy of liberty.

Almost no such books existed a generation ago. A rising tide of Americans is now aware that government, not the market, is the cause of inflation, depression and poverty. These people, no longer children of Roosevelt’s new deal, are waiting in the wings, even in Washington, to reverse the course of the American economy, to remove the ball and chain of big government which still consumes the days and years of our lives.

Even the academicians who have thus far turned to the government and defended it in return for favours to them, may come to realise that the Russian revolution which they have viewed so favourably is passé and that the real revolution, the revolution of 1776, of individual rights has taken place in their own land, unseen and unacknowledged by them.

The use of force by one government after another did not stop the clipper ships. In the end, they won the day and the wielders of governmental power had to go along or stagnate and die. In the same way, the soil of 1984, unlike the soil of say 1954, has been prepared for an outbreak of freedom which can pull even the welfare statists kicking and screaming into the 21st century and that is where we libertarians come in.

We are the intellectual spearheads of the coming renaissance of liberty. Just as the intellectual influence of the Fabians propelled Britain into socialism a century ago, so the intellectual influence of libertarians can turn Britain, and indeed the world, back to individual liberty because now the soil has been prepared.

The consequences of socialism in practise are increasingly plain for anyone with eyes to see. “It’s the essence of man,” said Aristotle, “to make decisions. His own decisions, not those made for him by others. To implement this simple but profound truth and to apply it over and over again, in its countless manifestations in our individual and social lives; that is our libertarian mission. Surely, it’s the noblest of goals and I see no good reason why we should not be able to achieve it.”

That was a typical John Hospers call to action.

FA Hayek

Who could not be influenced by FA Hayek? Hayek’s works can be described as a road map for the movement toward freedom and away from central planning.

Back in 1975 my friend Ron Kitching phoned from the other side of Australia and asked me if I had heard Milton Friedman speak in Australia during his visit that year. We both agreed that Prof. Friedman had injected a ray of light into Australia’s economic debate.

Kitching then said: “I think Australia is now ready for Hayek and I am expecting you to contribute some cash, along with Roger Randerson, Viv Forbes and a few other friends, so that we can issue an invitation and cover all expenses.”

Prof and Mrs Hayek visited in October, 1976 and he gave a series of lectures as well as an ABC Monday Conference program.

I have since valued personal time spent with Prof Hayek in Hong Kong in 1978 and in Berlin in 1982 and despite his intellectual stature, he appeared to enjoy talking with ‘mere mortals’ like me. He said that we are closer to reality than many academics and I know that he sensed the importance of his ideas being expressed in language to which everyone could relate.

Of course this was well before the implosion of communism in the Soviet Union and Central Europe and the turn to market economies there, as well as in Latin America, Asia and even Sweden. All this transformation is linked directly or indirectly to the work that Austrian-born Hayek had done during his long career spanning more than half a century.

Hayek had spent his long life relentlessly developing and promoting the thesis that state control of economic life cannot enhance human wellbeing; it can only bring misery and poverty.

On other occasions Prof Hayek reminded me of the important role that entrepreneurs should be playing in the battle of ideas. Once, I asked him to “slow down because I’m not an economist”, to which he replied, “I’m glad you are not an economist. We economists simply dream our ideas and think our thoughts but you go out and — fire the bullets!” I walked away from that meeting feeling that I had been given a useful role in society.

On another occasion, he explained to me why, quite often, I would find that academics dislike business people. He said that the big difference between business people and academics is that business people enjoy volatility, as they see it as opportunity, whilst academics crave certainty, such as tenure.

He mentioned that some academics feel it to be unjust that some business people are paid more than academics and that it drives them crazy to see business people happier than many academics. All these snippets of wisdom were passed on to me with Hayek’s typical tongue-in-cheek whimsical style and personally I have not experienced any conflict between academics and entrepreneurs.

Again, I value my personal correspondence with Professor Hayek.

HRH Prince Philip – Duke of Edinburgh

Prince Philip may not be as well known to you as the other three individuals I’ve mentioned but he was well known to all three of them. In fact, the Freeman Magazine (locate later) featured an excellent article on Prince Philip as an individualist.

In 1956 Prince Philip, a keen observer of industrialisation and its effect on individuals, realised that the three main community sectors, industry, trade unions and government, were not ‘talking’ to each other. He devised a plan to select 100 potential leaders from these three sectors and ‘lock them up together’ for three weeks — living together, travelling together and learning together.

This way, he felt that life-long bonds would be forged between ‘warring parties’ and the benefits would become obvious during subsequent years.

These conferences, held every four years, have generated over 2,500 well-connected individuals, still vigorously talking and learning from each other. It was my honor to be selected for the 1968 intake and it has given me the opportunity of sharing five experiences with Prince Philip, over the years.

In 1968, Prince Philip was ahead of his time with many of his words still ringing true today. He said: “Ideas are coming into Australia from the young people and unfortunately there is a time delay before they permeate through to the old. Don’t leave the change too long. Be tolerant but not permissive with our young. They are as much the children of their age as we were of ours.”

He taught us how to ask questions by reminding us that, the first time we ask anyone a question, we will only receive a polite answer. This is because they are unsure if we really want to know.

The second time we asked that question they will take us slightly more seriously and again give a partial answer. It’s only on the third time when we ask the same question, still being polite, that we will really get inside their mind and once they realize how serious we are they will open up and give us the true story.

Prince Philip said: “That’s the answer I want you to bring back to me, fully refined and fully focused.”

He recognised that a single approach didn’t suit everybody: “We can bring our children up by the book as long as we use a different book for each child.”

He asked us to think and speak as individuals and not just be a spokesperson for any organization or government. He told us to get over our great Australian distrust of excellence.

These were the two points that he wanted to leave us with. Firstly, that we should come to our own conclusions and act as an individual to avoid what is now termed ‘group-thinking’. He was so focused on individualism, that when he invited us to the Buckingham Palace 50th Anniversary Reunion he said: “… and you can’t bring your wives or partners because I’m not bringing mine.”

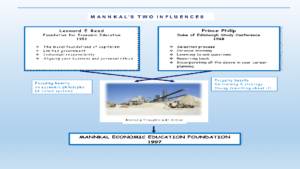

These comments, and the study tour itself, were behind my inspiration to set up our Mannkal Economic Education Foundation. Prince Philip’s personal training, for me, was a profound gift and the task of extending this profound gift lies with us who have been the beneficiaries.

Our Mannkal Economic Education Foundation program is a combination of the influence on all four of those individuals who I have mentioned but this slide put together, as you could imagine, by me as a mining person, indicates how, at that time, the first three influences Leonard Read, John Hospers and FA Hayek were heavy on philosophy but very light on strategy, whilst the Prince Philip input, to me, was completely devoid of philosophy with a 100 per cent focus on strategy.

What we, at Mannkal, have done is to blend philosophy on the one hand and strategy on the other hand, run them down through a crushing plant and screened to a size that just suits the task in hand. This is a photo of our finished product. This group of students were attending a Friedman Conference in Brisbane, Australia, last year.

Today I invite you to spend time, with our Mannkal Economic Education Foundation team, here in Canaria. So, after putting these thoughts and actions through our corporate crushing, screening and refining process, we are increasing our output of smart, questioning and useful young Australians. Over 1,000 so far.

Young people are interviewed and selected for events that will expose them (many, for the first time) to economic and political philosophic principles that promote the virtues of individual responsibility (which is difficult) as opposed to the (easier) alternative of ‘living off’ the efforts of unsuspecting taxpayers, many of whom are less well-off than the recipients of handouts.

This leads these young people to studies into the (often unintended) long-term consequences of many of today’s short-term legislative solutions and policy proposals.

‘Ideas have consequences’, particularly when applied to the study of ‘liberty’.

Liberty. It’s a simple idea, but it’s also the linchpin of a complex system of values and practices: justice, prosperity, responsibility, toleration, co-operation and peace. Many people believe that liberty is the core political value of modern civilization itself, the one that gives substance and form to all the other values of social life.

This year is Mannkal Economic Education Foundation’s 21st Anniversary. The momentum is building to the point where it is taking me away from my life-long involvement in mining and management and I enjoy measuring the results of our labours.

Why I’m an optimist

People ask me: “How can I remain an optimist when all around us we see deterioration in the standards by which we measure excellence? In business, in family, in education and particularly in politics.”

Politics is almost universally broken, beyond repair, (perhaps with the exceptions of Switzerland and Estonia). In many countries it is completely broken.

Here is why I’m an optimist.

Leonard Read taught me that life is not a numbers game, you don’t need the biggest gang to achieve your goals. History is full of examples of how small groups of individuals have achieved amazing results.

Leonard used the example of Christianity. He said, “Jesus only had a bunch of 12 in his team and one of them even turned out to be a treacherous bum.” More recently, in the late 1980s, three people with advice from a fourth, called the bluff on communism and communism collapsed.

That was achieved by a few telephone calls to the Pope from President Ronald Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. The calls could have gone like this:

“Good morning Pope. Our friend and economic advisor, Friedrich Hayek, tells us that Russian superiority is a myth and it will topple if we expose them for what they really are, just a bunch of frauds. Let’s pull the rug from under them and see what really happens.”

Now, that’s exactly what happened and Russia fell over, without a single life being lost too!

Those of us who were fortunate enough to have participated in the CATO Institute’s Transition to Freedom Conference, in Russia, in September, 1990, (Roberto Salinas Leon) would have experienced first-hand this Russian ‘myth of excellence’. They had become so focused on just a few national priorities that they couldn’t even make a ballpoint pen that worked, or a tube of toothpaste that didn’t squirt out the sides.

The 40 person CATO team, which I was so fortunate to be part of, were even asked to bring our own toilet paper with us, as Russia couldn’t even produce an acceptable quality of toilet paper. I even brought back a roll of Russian toilet paper and passed it around amongst my office staff saying: “Russian toilet paper was like Communism itself. Full of gaping holes.”

Today, we see Russia, again creating its own myth. We see Russia as a regional power, pretending to be a world power and getting away with it.

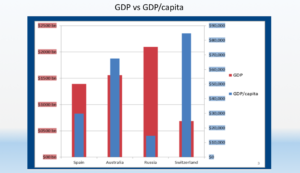

Russia’s economy is not much bigger than Spain’s or Australia’s economies.

Russia’s economy is shrinking whilst most other economies are growing and will continue to grow as long as we effectively promote the benefits of free, transparent trade with each other.

The strategic task of the Mont Pelerin Society and the Atlas Network of intricately related think tanks, around the world, if focused with laser-like precision, will concentrate the wisdom of our free market message into effective bullets for us to fire. We can win this ongoing war of ideas.

I know that the original founding members of the Mont Pelerin Society called themselves the ‘Remnant’.

In those darkest days, of World War II, it looked as though government central planning would remain with us forever. They set themselves the task of assembling the essential guidelines for a free market economy, in the hope that future generations would reach out for the ideas in an attempt to throw off the chains of central planning.

Their idea was simply to store all this wisdom in an intellectual time-capsule that could be opened by a desperate future generation. Fellow members — that future generation is us. We should waste no time in opening up that time-capsule.

These ideas have been further refined by subsequent intellectual giants, many of them here today, which now gives us an effective narrative with which to work.

We now have the ammunition so the focus must be on strategic execution, rather than simply maintaining our ‘Remnant’ role. We may have fed the troops from the comfort of our ivory towers but it is now time to move to the front line.

We need to experience the exhilaration of firing the intellectual bullets and decisively winning by focusing on what we can offer to individuals, rather than nations, by developing ‘bottom up’ strategies.

I believe we have the right people in this room to put this strategy together and see no reason for us not to win this crucial battle of ideas. I’m an optimist because there is a growing appreciation of the role of the free market entrepreneur. These entrepreneurs are impatient and have an essential part to play in overcoming intellectual inertia.

Academia must learn to love these free market entrepreneurs because without them we will be forever stuck in the time-capsule mode. The stakes are high and because of the quality of our ideas, all we need to do is lift ourselves up from being armchair observers and graduate into frontline activists.

Friends, let the battle commence.

3/10/18