There’s been increased interest in Croesus Mining NL of late. It was founded in 1986 and during my time with the company it produced 1.275 million ounces of gold and paid 11 dividends. It started with a staff of just two, including myself. Here’s a bit of background on what made it (when I sold it) Australia’s third largest Australian-controlled gold producer, approaching 300,000 ounces of gold per annum.

What’s in a name?

Croesus Mining NL was named after Croesus, who was King of Lydia (now Western Turkey) between 560-546BC. He was noted for his great wealth and also for the fact that he was the first ruler ever to mint gold coins. Like Croesus Mining NL, King Croesus had some good survival strategies but he overlooked a few small details. As a means of survival through good and bad times he formed many joint ventures with neighbouring countries in much the same way as we currently joint venture our mining properties.

Croesus Mining NL was named after Croesus, who was King of Lydia (now Western Turkey) between 560-546BC. He was noted for his great wealth and also for the fact that he was the first ruler ever to mint gold coins. Like Croesus Mining NL, King Croesus had some good survival strategies but he overlooked a few small details. As a means of survival through good and bad times he formed many joint ventures with neighbouring countries in much the same way as we currently joint venture our mining properties.

My old School of Mines colleague, Keith Parry, often mentioned in the early 1980s that I should stop joint venturing my mining properties out to other companies and actually “form your own company to do all the exploration yourselves and if you get the right people together you could be just like Western Mining Corporation before we lost our way.” Well, I did register Croesus Mining NL in 1982 and we were ready to move toward listing with some extensive properties at Polar Bear Peninsular near Norseman and just about all the Mount Monger Goldfield included.

The Croesus team grows

Well-known mining solicitor Chris Lalor agreed to be the Chairman. We were moving toward listing when a former non-performing joint venture partner, White Industries, announced that they intended to exercise their ‘pre-emptive right’ over the property. Once they knew what we were doing with it, they thought they should do the same and they were moving toward putting the property into their own float, AUR NL. I had several robust phone discussions with Travers Duncan (White Industries) where I politely mentioned to them that they had relinquished their interest and had never had a ‘pre-emptive right’. However, they responded that they had their own in-house solicitors and they had more money than me and, from this, I knew that resolution would probably be some time away. So I moved the Mount Monger areas into another public company called Mistral Mines NL and became its Exploration Director, until such time as I had gathered together the replacement ‘land package’ for Croesus Mining.

This took until late 1985 and by that time Chris Lalor was thoroughly occupied with his new role in Sons of Gwalia and I replaced him – albeit as Executive Chairman. We listed in July 1986, the only company to float in that miserable year, with three well-known brokerage houses backing the float. Just for interest let me mention who they were:

- TC Coombs of London as underwriters

- May & Mellor, leading Melbourne stockbrokers

- Ray Porter & Partners from the Perth Stock Exchange (which was quite separate to the other Australian Stock Exchanges at that time).

It’s interesting to reflect that none of these names exist today – an illustration of how volatile many aspects of our industry have been and will remain.

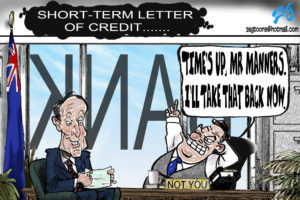

Can I borrow a Letter (of Credit)?

We raised $2m which we promptly spent on enthusiastic exploration which, to our disappointment, produced no mineable deposits anywhere. At that point I realised the need for a cash flow. I saw an opportunity when CRA (Rio Tinto) announced that their Goldfields Region prospects were all for sale as they had decided to move out of gold. I saw this as a great opportunity for Croesus and promptly headed to Perth for CRA’s head office to ensure that we were on the tender list. They and their advising bankers would not include us as we “had no credit rating”.

So, I walked up the Terrace to Westpac Bank and explained that we could not get on the tender list without a Letter of Credit from Westpac. Westpac, realistically, explained why they had some difficulty in issuing a company, who had just run out of money, with a Letter of Credit.

With tongue in cheek I asked how much they would charge to actually lend me a Letter of Credit until noon the next day. They hurriedly had a meeting in the next room where they probably had a good chuckle and returned to advise that they would charge me $25,000 to lend me a Letter of Credit until noon the next day. That’s all I needed. The next morning I marched up to CRA’s office proudly displaying this document and was consequently included on the tender list. They alarmed me by wishing to keep the Letter of Credit and I explained that it was mine and not theirs, but they should feel free to keep a photocopy of it. They found this to be satisfactory and I managed to get the Letter of Credit back to Westpac at one minute to noon!

With tongue in cheek I asked how much they would charge to actually lend me a Letter of Credit until noon the next day. They hurriedly had a meeting in the next room where they probably had a good chuckle and returned to advise that they would charge me $25,000 to lend me a Letter of Credit until noon the next day. That’s all I needed. The next morning I marched up to CRA’s office proudly displaying this document and was consequently included on the tender list. They alarmed me by wishing to keep the Letter of Credit and I explained that it was mine and not theirs, but they should feel free to keep a photocopy of it. They found this to be satisfactory and I managed to get the Letter of Credit back to Westpac at one minute to noon!

Our tender offer for the CRA areas was $20.3m or 2.5 per cent higher than the highest bid, whichever was the higher figure. They pointed out that this was a non-conforming bid but I managed to convince their banking advisors that their prime responsibility was to obtain the highest figure possible for their clients, and on that basis they should honour that commitment. At the conclusion of the tendering process we walked away with that prize which, in my mind, mainly consisted of the Hannan South Mine.

There is quite a story on how we managed to pay the 10 per cent deposit by 10am the morning after winning the tender and finance the entire purchase within the 21-day prescribed period and managed to repay all the loans from gold production within nine months. With much help from an enthusiastic board, staff and well-chosen consultants, with special mention of John B Oliver and HM (Harry) Kitson, Croesus Mining NL embarked on a productive and profitable 20 year adventure where we mined 25 open pit and two underground gold mines and paid 11 dividends to our supportive shareholders.

Croesus Mining: Gold Company of the Year

The ill-advised so-called Native Title Act came into being as we were developing the Binduli mining area just south-west of Kalgoorlie and we ended up with eight competing claimants over that area at a time when we were all ready to build a new mill and feed it from several open pits. The eight claimants were basically all members of the same family and I could already see the nonsensical frustration that lay ahead of our industry.

Our mill never got built. The plans are still in plan cabinets so to stay in business we high- graded the mine and trucked the ore to our Hannan South Gold Operations. I estimate that Native Title delays cost Croesus Mining $26m and that, to us, was a lot of money. The money didn’t go to anyone, it was just that the gold was never produced. I was not enjoying these non-mining frustrations that were encroaching on our industry and at that point decided to sell my interest in Croesus Mining.

An interesting process emerged to find the most suitable incoming major controlling shareholder and our advisors had identified eight suitable companies. This was a most interesting and complex procedure but one that I would recommend to any major shareholder planning to depart a public company. Somewhat similar to planning your own corporate funeral.

The winning team

I brought senior staff into my confidence throughout this entire process and I was asked what I would do if I found that the best offer, to guarantee the future of the company and the fantastic team we had put together, was not found to be the same offer that gave me the highest dollar amount. This, in fact, was the case and it actually cost me a quarter of a million dollars, but I felt the outcome was worthwhile. The incoming Canadian company, Eldorado Gold, were really acquiring a first-class technical team that they wished to deploy to Indonesia and participate in some new generation discoveries, i.e. Bre-X.

Part of my contract with the incoming Eldorado Gold was that I would go on their Board and would cease being Croesus Executive Chairman within six months of the transaction and leave the company within two years. The events that unfolded made this extremely difficult. However, I had already moved out of Kalgoorlie to Perth and reactivated my family company which for several years been capably operated by my co-director, Harry M Kitson.

The eleventh and last dividend that Croesus paid was rammed through by me, much to the protests of senior staff. I felt, at that stage, that the cash would be more usefully utilised by the shareholders rather than left at the disposal of the new crop of executives. This due to a series of tragedies including a Norseman death, gold stealing charge and a decline in respect and mutual trust.