This was a speech given at UWA’s ECOMS function in 2008.

I’m with the band

One of the most satisfying experiences I’ve had was playing the jazz clarinet in a Kalgoorlie pub every Wednesday night. I enjoyed the total focus that it required, shutting out the outside world and becoming lost in the creative process. It wasn’t a matter of getting 51 per cent good notes or more, and 49 per cent or less bad notes, it was a matter of only remembering the magic of the good notes.

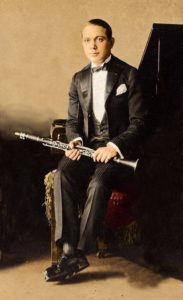

An early influence on my clarinet playing was a New Orleans clarinettist called Leon Roppolo. His style was restrained, even melancholy, playing much of it in a low register, in a true minor style closely related to Sicilian and Neapolitan melodies.

An early influence on my clarinet playing was a New Orleans clarinettist called Leon Roppolo. His style was restrained, even melancholy, playing much of it in a low register, in a true minor style closely related to Sicilian and Neapolitan melodies.

Of course jazz is a wonderful hybrid music made up from many sources. Rappolo’s playing influenced many early-day musicians, including clarinettist Benny Goodman who went onto make quite a name for himself. However, Rappolo wasn’t terribly strong on articulating his thoughts clearly and he was somewhat eccentric and was seen, during any heavy winds, leaning with his ear against a lamp post listening to the harmonies that the wind created blowing through the electric cables and he’d be playing his clarinet superimposing wonderful melodies over these harmonies.

In the end they simply took him away and locked him up in a mental institution where he formed his own jazz band and ultimately died in a mental home in Louisiana.

Why am I telling you all this? Well, it’s all about outcomes, and that’s what economics is all about. Often well intentioned people thrust us into short term programs whereas the long term outcomes are often the opposite to their original intention.

Now, think of two alternative outcomes to the Leon Roppolo story:

- If he had have been more articulate, as all you folk no doubt are, he would have quietly reasoned with his captors and had them listen to the harmonies coming down the light pole and they would have left him alone, free to pursue his creative callings.

- Or, he may have been a politician who had access to tax funds so he could employ a huge army of media and public relations consultants to convince us that leaning against a lamp post with a clarinet was indeed a very fine thing to do and in fact he may have even passed a law to make it compulsory.

The responsibility of knowledge

Now when you leave this university with an economics degree, you will leave with a tremendous responsibility and a challenge. Your degree will imply that you have been taught to think and reason, and continually question the status quo. You will listen to news items and be able to clearly identify who the winners and losers are, from every new piece of legislation. It will become clear that every government interference in the economy consists of giving an unearned benefit, extorted by force, to some people, but always at the expense of others.

But where will your economics degrees lead you? I cannot answer this question for you, but I can guarantee that you will venture down paths least explored into outcomes beyond your dreams.

I do know that I spend a lot of time preparing myself for a future that never happened (in my case electrical engineering) but instead continually got side-tracked into better options so that now each day, when I wake up, I just simply feel so lucky I look around to see who I can thank.

My next book, my fourth, titled Heroic Misadventures, should be out before Christmas and it’s not the usual success story book on ‘how to do it’. It’s really about a series of misadventures that took me in entirely different directions.

Packing up

I won’t go into many details here as I’d rather you bought the book, however, it does mention how, at the age of 15, after school, when working in my father’s engineering business, opening large pine crates containing mining equipment from the USA, I used to smooth out some of the crumpled packing papers and read material from the Foundation for Economic Education in New York. That was my introduction to the thoughts of economists Mises, Hayek and Friedman, and many others.

Several years later when I used some of this material as Editor of the Kalgoorlie School of Mines Student’s Magazine I nearly got run out of Kalgoorlie as it was a highly unionised town at that time.

I wrote to the President of the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE) and told him that their ideas weren’t much good as they were getting into trouble, he kindly took the trouble and patience of writing back to me explaining that there was nothing wrong with their ideas but that if I was going to take any sort of stand I should become thoroughly conversant with the principles of free enterprise and be in a position to conduct an intelligent debate.

At that stage, when I was about your age, I had not idea or concept that all that stuff that I enjoyed reading so much, would lead me to interesting international events, and connect me to such a vital network of people that I enjoy and admire.

This has included participation in many interesting historic events, ranging from the lead up to the German reunification, the collapse of the USSR and the Hong Kong handover. Venues for such conferences have ranged from Washington, London, West and East Berlin, Zurich, Mexico, Iceland, Canada, San Francisco, and next month in South Korea and Japan (with one of your UWA students, Callum Jones, also attending as a Mannkal scholar as a winner of one of the Hayek essay contest awards.)

I had no idea that I would be a member of the CATO Institute’s team participating in the Transition to Freedom seminar series in Moscow and St. Petersburg in September, 1990, to prepare them for free enterprise which was arriving the following month, or that I would be a host to Margaret Thatcher at the Waldorf Astoria dinner in New York in 1996.

My favourite economist

Another interesting side-issue was that I noticed that all of my favourite economists had a soft spot for philosophy, so in 1961 I signed up for a Philosphy One course here at course here at UWA. The text book An Introduction to Philosophical Analysis by American Professor of Philosophy, John Hospers.

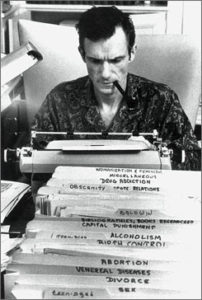

I was struggling a bit with the book but then an Australian magazine called Pix, also in 1961, got hold of a copy of the book and published a feature article with the bold headline “This textbook is unspeakably evil”. Well, this gave me a reknewed interest in the book and shortly after a fellow called Hugh Heffner published The Playboy Philosophy, which made me realise there was much more to philosophy than was initially apparent.

But back in 1961 I had no idea that some years later John Hospers and I would become very good friends, corresponding regularly and meeting in the most remarkable places and the last time was in 2004 where he spent the full day with my wife, Jenny, and I as our tour guide at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in California.

More recently, I also had no idea that I would be in Queensland last week asking a question of our Federal Treasurer that he was unwilling to answer. Or, that during the same visit to Queensland, I would meet a charming young Somalian lady, Ayaan Hersi Ali (author of the best selling book Infidel) and that we would share Hayek stories on how his ideas crystallised a lot of our own thoughts. I certainly had no idea where all this would lead and I’m not simply boasting or name-dropping, I’m just amazed that one thing so logically leads to another, once you build up a bit of momentum to your life.

I feel now that I’ve prepared myself for the next challenge, whatever that may be, but fortunately I welcome challenges.